|

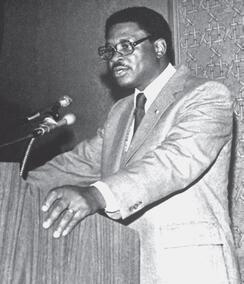

SHORT EXCERPT FROM MY BOOK, "UNLESS WE TELL IT...IT NEVER GETS TOLD!" AND CLANZEL THORNTON BROWN. JACKSONVILLE'S BLACK HISTORY!

The name of Clanzel Thornton Brown Sr., will not appear in most critical histories of the Civil Rights Movement in this country generally, nor in Jacksonville, Florida, specifically, but it should. His influence in Jacksonville, and this country, was certainly felt when he served as executive director of the Jacksonville Urban League, and it is still felt today. Clanzel was more than a friend to me. He was a close confidante with whom I spent many hours discussing Jacksonville’s myriad problems and their possible solutions. It is difficult to write about a friend who gave so much to his community and one who died much too early. It is more difficult recalling the memories of what that friend meant to the community he served. But I am not writing about Clanzel T. Brown because he was a friend. I am writing about Clanzel T. Brown because of what he represented to the Jacksonville community and this country. (Special note- My late brother-in-law, Frank Priestly served as Chairman of the Jacksonville Urban League Board during Clanzel's directorship.) Clanzel was convinced that the key to achieving social parity and civil rights for Blacks was fighting for economic inclusion, educational achievement, and civic engagement, long before civic engagement became the buzzword it is today. It was said that “Clanzel had but one enemy—and that enemy was poverty.” Clanzel was one of this country’s unsung warriors in the “War on Poverty.” Those of us who worked for the anti-poverty program, or worked with that program, or worked in other community programs fighting poverty, would laughingly invoke Billy Preston’s words from his epic hit, “Nothing from Nothing” when he sang “I’m a soldier in the War on Poverty.” If many of us, like Ervin Norman, Dr. Harold Childs, Earl Sims, and Jacqueline Jackson, were considered soldiers and officers in that war, then Clanzel Brown, like Moses Freeman and Alton Yates (former executive directors of Jacksonville’s anti-poverty programs), were War on Poverty generals. Over the years Urban League directors in this country were thought of as somewhat conservative, as opposed to being on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement, and they were also considered somewhat single-task-oriented, with jobs as their priority. Clanzel saw a much larger picture. Clanzel’s commitment was to improve the lives of Jacksonville’s Black citizens during the civil rights struggle of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. During his tenure at the Urban League, he created programs that encouraged and recruited Blacks to apply for jobs in the City of Jacksonville’s police and fire departments; he was a moving force to add Blacks to the construction industry by developing the Jacksonville Hometown Plan (funded in part by the U.S. Department of Labor); he developed many pioneering youth programs; he established one of the premier housing programs in the country; and he spearheaded the Urban League’s “State of Black Jacksonville Report” in 1977, using research and data as instruments for measuring progress or the lack thereof in the lives of Black people. The “State of Black Jacksonville Report” became an annual review of social and economic metrics, as well as prescriptive recommendations for improving the lives of Blacks in the city. It was not unusual for Clanzel, as executive director of the Urban League, to receive invitations to meetings that dealt with job training, unemployment, under-employment, civil rights, and equal opportunities, with everyone from the Jacksonville Chamber of Commerce to the City of Jacksonville to local ministerial groups. What was striking was that, if Clanzel was not able to attend the meeting for whatever reason, there would be reluctance on the part of the meeting’s conveners to proceed without their knowing if Clanzel was “on board.” What a testimony to his influence! Former president of the National Urban League John Jacobs said that Clanzel, who he had previously tapped to work with Urban League affiliates in other communities to help grow them, built the Jacksonville Urban League into the best in the nation, and, although his stay was brief, he made every minute count. Clanzel was the executive director of the Jacksonville Urban League when both Whitney Young and Vernon Jordan were the executive directors of the national organization. Young, a recipient of the 1969 Presidential Medal of Freedom, was a stalwart civil rights leader of this country until his untimely death in 1971. He would frequently refer to the Clanzel-led Jacksonville Urban League as a “star,” and many felt that Young was grooming Clanzel to eventually take his place. Vernon Jordan became the National Urban League’s executive director following the death of Whitney Young, and would request that Clanzel provide input and advice at meetings in New York and Washington. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed Clanzel to the National Community Advisory Investment Board. Clanzel T. Brown was a mentor before mentoring became a commonly known concept. But Clanzel was much, much more than just a mentor. Clanzel Brown was a leader, and a difference-maker, who believed in people: Black people, white people, young people, old people, rich people, poor people —just people. From the day he became director of the Jacksonville Urban League in 1965, he saw the need to cultivate a cadre of young people who could be the brain trust of the local community. The list is extensive, beginning with C. Ronald “Ronnie” Belton, the City of Jacksonville’s chief financial officer; Ronnie Ferguson, former president and CEO of the City of Jacksonville’s Housing Authority; and Ken Johnson, former legislative aide to Congresswoman Corrine Brown, and senior policy advisor for military affairs to former Mayor Alvin Brown. I sat down with three of Clanzel’s four children— Clanzenetta, Clanzerria, and Clanzel II (Clanzel’s youngest son, Clanzedric, was in Iraq working in a civilian job when we met and was thus unable to participate)—around the kitchen table at the home of Clanzenetta and her husband, Lee Brown, for a retrospective look at the impact their father had on the Jacksonville community. Although I have known all of them almost since birth, I wanted to hear their words and their recollection of when they recognized how significant an impact their father had on the Jacksonville community generally, and the Black community specifically. Of course, they all have the memories one would expect of children who lost their father at a young age. Yet, they were mature enough to understand what their father meant to Jacksonville as the Urban League executive director and as an advocate for the Black community. Clanzel Brown II, Clanzel’s oldest son, and a licensed construction contractor answered first. “One day when I was about twelve or thirteen, we were in the barbershop. It seemed like whatever conversation came up in the barbershop, the men would always ask my dad what he thought or to explain the situation to them. Dad would take the time to explain all the scenarios of an issue. Even if the conversation had started as an argument when he finished there was nothing left to say. I began to realize my dad was very special.” Clanzerria is Clanzel’s second daughter. “I knew my daddy was special when I realized that he always wanted to try and help everyone; he never seemed to say ‘No.’ My sixth-grade math teacher, Mrs. Margaret Day, and my sixth-grade English teacher, Ms. Jacque Parker, would often speak to me about some of the things Daddy was trying to do to make Jacksonville better for all people and how important education was, not only to strive, but to achieve. It was as if my dad was a teacher because everything he taught us at home was always reiterated by my teachers. As I think of my dad, he was a teacher. “People would often come to the house to work on programs and projects through creating job-training programs, or getting involved in making their neighborhoods safer, or encouraging community consciousness through engaging dialogue and discussions about how their voice matters in their community and how economic development provides opportunities for a better quality of life in Jacksonville.” Clanzel’s oldest daughter, Clanzenetta “Mickee” Brown, shared her feelings with me during the same week her son graduated from Florida A&M University. Her father had also graduated from FAMU fifty-five years ago, so it was a tearful yet significant rite of passage, a grandson following in the footsteps of his grandfather. It was even more tearful for her to share her feelings and her recollections about her father, the poignant opening up of a closed wound. She started by saying, “This was hard to do. I thought I could whip it out, but it kind of got me down.” “When I was a young girl, I knew my father was important if not special to the community because people would be overtly attentive to him and our family. Everyone seemed to know him wherever we went, and at the beginning of my school year, teachers always asked if I was ‘Clanzel Brown’s daughter.’ Instead of this giving me a ‘princess complex’ it made me determined not to embarrass my family, particularly my dad. During my teens, I began to understand my father’s politics and his socioeconomic worldview because he was often approached by the media. We’d see Dad on television, hear him on the radio, or see him quoted in the newspaper, regarding pressing community issues like economic disparity, police brutality, poverty, and access to quality education. He provided measured but powerful insights. After his death in 1982 I left Jacksonville to attend college and I’ll admit that I missed being ‘Clanzel Brown’s daughter’ when I was in a place where his work was not as well known. I’d go to the university library and read the Ebony magazine article about Jacksonville’s prominence in the ‘new South,’ in which he was prominently featured. “After returning to Jacksonville, I became a volunteer at Jacksonville Community Council, Inc. (JCCI), in 2001. While working at JCCI, I began to understand the impact that my father had on the community. I was a staff resource during a JCCI race-relations study. Over six months, many persons who worked on the study told me how important my dad had been to the city and to them personally. The co-chair of the study committee, a prominent Black judge, told me how he had personally benefited from a Jacksonville Urban League program during my dad’s tenure. I also dis- covered that my father had been a board member of JCCI. A signal moment for me occurred when JCCI began publishing its annual “Race Relations” report card in 2001, and I recognized that it was a successor to the annual “State of Black Jacksonville Report” that my dad had initiated back in 1977. I even had the privilege of working on the JCCI report card with my dad’s good friend Rodney Hurst [the author of this book]. “As writing, research, and planning consultant, I’ve had the privilege of working for a variety of organizations, including the Jacksonville Urban League, and I frequently run into individuals who worked with my dad to build a more equitable city. From time to time I’ll read a snippet about him in local history books. I regularly drive past the city park that bears his name, and every year the Urban League honors a local citizen who exemplifies his spirit. My dad made a difference because he impacted the next generation of leadership in our community. Jacksonville is far from perfect, but it’s a much more diverse and integrated community because of the people who fought against racial injustice and inequality during the last half of the twentieth century. My dad was one of those folks and I stand on his shoulders.” Clanzel tragically died of heart failure on July 13, 1982, much too young at age forty-nine. His enduring influence and legacy rest in his extensive work, the goals he accomplished, those whom he influenced, and his “people investments.” His legacy is epitomized by the award named in his honor and given every year by the Jacksonville Urban League. (Author’s note: I am a recipient of the Clanzel T. Brown Award.) His legacy is perceptible in those he mentored and impacted and those who continue to carry on an Urban League experience defined by his well-known philosophy of “helping the least among us.” His legacy is also reflected in the faces and lives of four young adults who love him, cherish his memory, and understand that their father was a respected and revered community leader who simply made Jacksonville better. Clanzel T. Brown’s legacy is that of an ordinary man who simply accomplished extraordinary things! And for that, we are eternally grateful.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorRodney. L. Hurst, Sr. Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RODNEY L. HURST, SR. - THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed