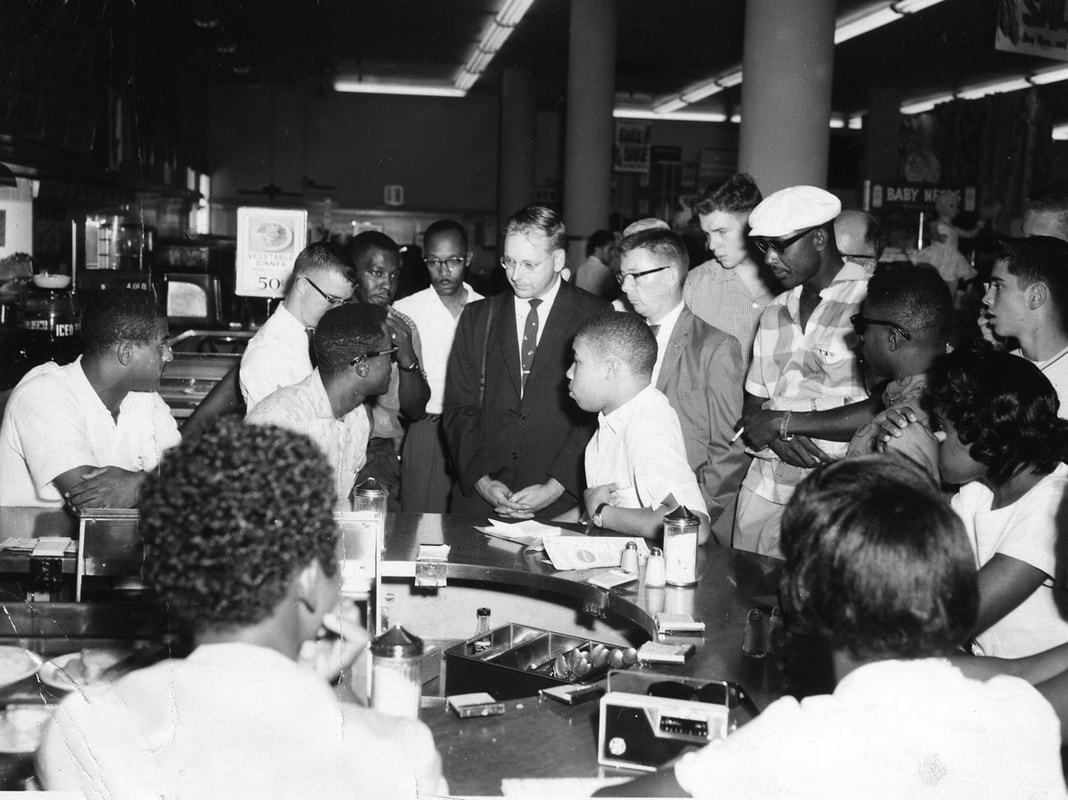

This is the 60th Anniversary year of the 1960 Sit-In Movement. On February 1, 1960 four college students from HBCU, North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, North Carolina... David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., and Joseph McNeil ...challenged the insulting segregation and racist disrespect in Woolworth's retail store, which wanted you to spend your money but only where they wanted you to be spend your money. That first "sit-in" inspired a wave of sit-in demonstrations which challenged segregation and Racism by targeting White lunch counters, which were veritable vestiges of segregation and Racism, and spread to more than 55 cities, including Jacksonville (August 13, 1960). Jacksonville's local White press blacked-out all local news about the sit-ins in Jacksonville. Thank God for the National Black press and locally the Florida Star, which reported major portions of the real story of the Sit-in Movement. My book, "It was never about a hot dog and a Coke!" which I wrote as "my personal account" of what happened as the President of the Jacksonville Youth Council NAACP and a leader of the Sit-ins, has now become a history book of sorts because you will not find the information, material, and pictures in the book any place else. The following is a short excerpt from "It was never about a hot dog and a Coke!" detailing what Really Happened. Chapter 9 August 27, 1960—Ax Handle Saturday “There is no medicine to cure hatred.” —African proverb "Mr. Pearson received several calls on the morning of August 27, 1960 about very suspicious and unsettling activities in Hemming Park. He contacted Arnett Girardeau and Ulysses Beatty and asked them to ride with him downtown to Hemming Park. “As we approached Hemming Park,” Girardeau recalled, “we saw several white men wearing Confederate uniforms. Other whites walked around Hemming Park carrying ax handles with Confederate battle flags taped to them. A sign taped to a delivery-type van parked at the Duval and Hogan Streets corner of Hemming Park read, ‘Free Ax Handles.’ Small fence rails with shrubbery bordered that section of Hemming Park. [As we drove by,] we could see bundles of ax handles in the shrubbery. . . . No one attempted to conceal them. “We also saw three police[men] separately riding three-wheel police motorcycles. We watched as the police talked to the men dressed in Confederate uniforms. It appeared they were simply having a conversation. Certainly, [the police] were not questioning [the men]. As we circled Hemming Park, the police left.” We arrived at the Youth Center the morning of August 27, 1960 unaware of the Hemming Park activities. We opened our meetings with our usual prayer, not expecting this morning to be any different from other mornings. We sang our usual songs, including “We Shall Overcome.” Though our meetings became serious after we started the sit-in demonstrations, this meeting had a more serious bent. Mr. Pearson explained to us what he, Girardeau, and Beatty saw that morning at Hemming Park. He described the white men wearing Confederate uniforms, and other white men with Confederate flags taped to ax handles. He told us about the free ax handles sign and warned, “There could be trouble today.” He tried to contact Sheriff Dale Carson to express his concerns, but didn’t reach him. Mr. Pearson said he would understand if any Youth Council members decided they did not want to demonstrate that day. We openly discussed our plan of action that day, and whether we would sit in. On the heels of the situation with Parker, we figured we would be facing the Ku Klux Klan in Hemming Park. Several Youth Council members said we should cancel the day’s demonstration. We tried to stay strong and courageous and move forward. Yet a healthy fear of the unknown played a big role in our conversation. My current pastor, Reverend (now Bishop) Rudolph W. McKissick Jr. defines “healthy fear” as knowing the seriousness of your situation, which is an appropriate characterization of how we felt that day. Sometimes, when you face a situation like that the Youth Council faced that Saturday, you rein in the impetuosity of youth. Sometimes, the situation tests youthful mettle and resolve. Fear on one hand, and our interpretation of courage on the other, played a big part in whether or not we would demonstrate. I cannot really say what won the most points to demonstrate. Appropriately, we made our final decision after Mr. Pearson led us in prayer. We always joined hands and prayed at the beginning and the end of all Youth Council meetings. After the prayer that ended our meetings, we would say, “Together we go up, together we stay up”! Corny sounding perhaps, yet the times dictated we do everything in our power to reassure each other and reconfirm our faith in God. After prayer, I took the first of only two votes by Youth Council members on whether or not to demonstrate. We voted unanimously to demonstrate. Someone defined courage as continuing forward even as fear tries to hold you back. Our determined courage overcame our healthy fear. However, instead of sitting in at Woolworth, in front of Hemming Park, we decided to sit in at W. T. Grant Department store, three blocks away from Hemming Park at the corner of Adams Street and Main Street. After the vote that Saturday, there were 34 demonstrators, including Arnett Girardeau. Though he was older than most Youth Council members, we decided to select Arnett as the sit-in captain because of our view that Arnett could better handle an awkward situation, if one occurred. No one quarreled with his selection. The W. T. Grant Department store had a lunch counter, though it was not nearly as large as the one at Woolworth. Like Woolworth’s, Grant’s also had a “colored lunch counter.” When we walked into Grant’s, I remember seeing four police officers directing traffic at the corner of Main and Adams—or so it appeared to me. fter we sat at Grant’s white lunch counter, store officials summarily closed and turned out the lights—all usual and customary. When we came out of Grant’s, and turned west on Adams, we could see in the distance a mob of whites running toward us. As the mob got closer, it became obvious they were swinging ax handles and baseball bats. In a surreal scene, they swung those ax handles and baseball bats at every Black they saw. It is amazing what the mind’s eye captures during tense split-seconds of confrontation. I remember seeing a television reporter or a camera operator from local television station Channel 12 on top of a car taking pictures—until someone knocked him off the car with an ax handle. Employees of stores along the block started locking store doors. If you were inside a store, you stayed inside; if you were outside a store, you could not get in. We had tried to prepare for most scenarios to be encountered during sit-in demonstrations, but nothing prepared us for an attack as vicious as this. Although we would laugh later about trying to be cool while looking at those attacking us with ax handles and baseball bats, surviving the onslaught became our primary concern. Most people have held or felt a baseball bat, but not an ax handle. Ax handles usually are as heavy as a baseball bat and can inflict as much damage. They are made of solid wood sturdy enough to hold an ax, and you never forget its look in the hands of someone trying to maim you. All of us started running and trying to protect ourselves, but Black downtown shoppers were simply no match for those wielding the baseball bats and ax handles. Some fought as best they could, but most simply tried to run for safety. In its September 12, 1960 issue, Life magazine captured the most vivid image of the attack’s aftermath. Several whites are shown attacking Charlie B. Griffin, a friend and a classmate who graduated in 1961 from Northwestern Junior Senior High School. The picture, though in black and white, graphically shows Charlie in his blood-drenched shirt standing next to a law-enforcement official. Charlie played high school football at Northwestern and, given his size could have ably defended himself in a fair fight. But Charlie became another victim of the racial attacks in downtown Jacksonville that day. The attack on Charlie, it so happened, occurred SWB (Shopping While Black). He was not a member of the Youth Council and was not “sitting in” that day. He would later tell me that as he walked downtown, “this white guy” ran toward him and took a swing at him with an ax handle. When Charlie started to defend and protect himself, more whites came to hit him with ax handles. The attacks against Charlie and the other Blacks that day were vicious and cowardly. As for me, I ran to Main Street first, which is away from the mob, and then north on Main Street to wherever I thought I could find safety. We were on our own—we had no police protection. All law enforcement officers had disappeared. Afterwards, we came to believe that the Jacksonville Police Department and the Duval County Sheriff’s Department knew in advance that racial violence would occur on August 27, 1960. As I ran down Main Street, I was picked up by a woman who drove me to the Youth Center. To this day, I cannot remember her face, although Mrs. I. E. “Mama” Williams would later tell me she had been the one to pick me up. I just remember the person asking me if I was hurt and telling me she was a member of the NAACP. Forty years later, I would find out how much Jacksonville and Duval County law enforcement knew about what would happen that day. I met Clarence Sears, an FBI informant with the Ku Klux Klan during the period leading up to Ax Handle Saturday, at the 40th year Ax Handle Commemorative Anniversary Program at Bethel Baptist Institutional Church. I did not know Clarence Sears at the time, but he painted a very descriptive timeline of the events leading to Ax Handle Saturday. His CI (Confidential Informant) nickname was Charlie. Sears gave his report to his FBI manager, who in turn gave the report to Sheriff Dale Carson, or, to be absolutely accurate, put his report on the sheriff’s desk. Supposedly, a police officer in the sheriff’s office intercepted the report and gave it to the head Klansman, a so-called Cyclops. Sears said the report caused quite a commotion at the next Klan meeting. The Klan realized, according to Sears, that there was “a traitor in our midst,” but never knew his identity. According to Sears, the Klan intended the attacks to spark a citywide racial riot."

0 Comments

I am glad the Kansas City Chiefs won the Super Bowl, and NO...I did not watch the Super Bowl. But their win will be insignificant if they do not understand ...especially the Black players...the big picture of visiting a Racist president in the White House, who is on public record insulting Black NFL players, and by extension Black folks in this country. The incompetent Racist called those Black NFL players who knelt protesting Racism and police brutality, "Sons of Bitches" ... in addition to saying Blacks and Browns come from "shit hole countries."

I am waiting for the "there is no politics in sports" BS. There is politics in everything in the American discourse and there is Racism in that discourse. In a recent news article, Black players on the Chiefs felt it is no big deal "rubbing elbows" with a Racist president. Some of their comments were sad...not surprising, but sad. I also tire of Black folks giving White folks accolades in the sports arena as a great coach...or whatever...but give them a pass when it comes to Black human dignity and respect. You want Blacks to go into battle on the athletic field, but you will not go into battle on the "human respect field." Andy Reid might be a great NFL coach, but his lack of respect for his players is showing. When you visit the White House knowing a Racist has desecrated the office with his Racism vitriol, what does that make you? There are no excuses. Being a Bent Back Negro does extend to sports. The Struggle Continues! |

AuthorRodney. L. Hurst, Sr. Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RODNEY L. HURST, SR. - THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed